I was sitting in a conference room at a company retreat, nursing a lukewarm coffee, when the guest speaker launched into a story I’d heard a dozen times.

He was a charismatic consultant, brought in to talk about disruptive innovation. To make his point about the stifling nature of rules and legacy systems, with a charm, he began the tale of the two horses’ asses.

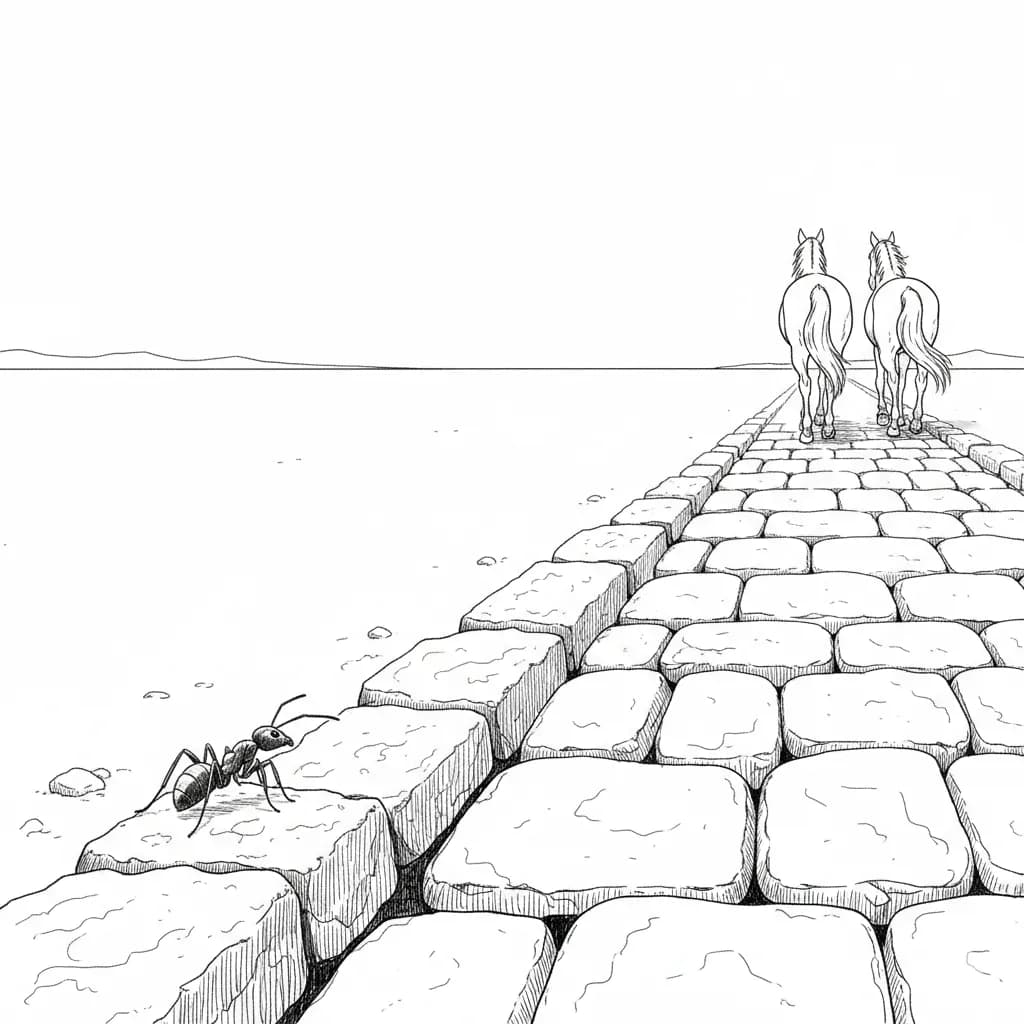

The story, as he told it, was a perfect parable. It traced an unbroken, two-thousand-year line from the width of a Roman war chariot to the design of the Space Shuttle’s rocket boosters.

The room nodded along. It’s a seductive myth because it feels true. It has a clear villain—mindless adherence to the past - and it confirms a deep-seated bias among creative people that standards are the enemy of progress.

It’s a simple, memorable anecdote that gives us permission to resent the constraints we work under.

But here’s the problem: the story is not just factually incorrect - the lesson it imparts is a dangerously flawed foundation for building an innovative and resilient organization.

I’ve spent my career as an engineer and now as a Head of Engineering trying to build systems - both technical and human - that can create amazing things.

And I can tell you that this myth gets it completely backward. This is the story of how I learned to stop worrying and love the right kind of standards and why that philosophy extends from our code architecture to the most important standard of all: how we treat our people.

Table of contents

Open Table of contents

Part 1: The Myth Under Microscope

Before we can build a better foundation, we have to demolish the old one. The “two horses’ asses” story is so compelling because of its grand, sweeping narrative. It goes like this:

The standard U.S. railroad gauge is an odd 4 feet, 8.5 inches. This is because the first U.S. railroads were built by English engineers who used the English standard. They used that gauge because the first rail lines were built by the same people who made pre-railroad tramways and they simply used the same jigs and tools. Those tramways had that specific wheel spacing to fit the ruts in England’s old, long-distance roads, lest the wagon wheels break. Those roads, in turn, were built by Imperial Rome for their legions. The ruts were first formed by Roman war chariots, which were all built to a standard width. And why that width? Because they had to be just wide enough to accommodate the back ends of two war horses.

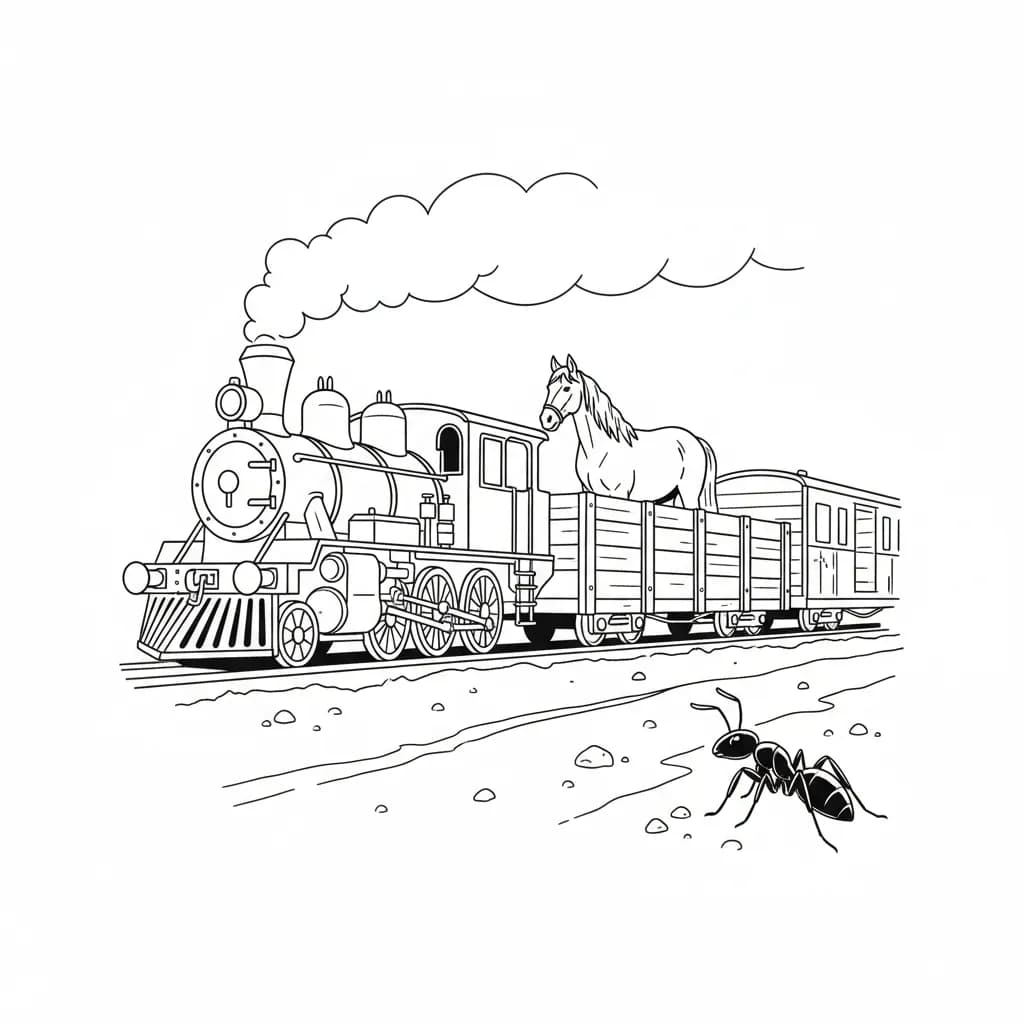

The story culminates with a modern twist:

the Space Shuttle’s Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs), built by Thiokol in Utah, had to be shipped by train to the launch site in Florida. The railway line passed through a mountain tunnel that was only slightly wider than the track. Therefore, a major design feature of one of the most advanced transportation systems in human history was ultimately determined by the width of two horses’ asses.

It’s a fantastic story. And it’s mostly wrong.

Fact-checking sites have thoroughly investigated this legend and found that while it contains kernels of truth, the causal chain is broken in multiple places.

First, the Roman connection is more coincidence than causality.

The width of a cart pulled by two horses in harness is a practical, physical limitation that emerged independently in many places. It’s a “prosaic” link, not a direct line of imitation.

Evidence for this is that rail gauges are not uniform across the former Roman Empire, which you would expect if the ruts of Roman roads were the single determining factor.

The real origin of the standard gauge is more pragmatic and much less ancient.

George Stephenson, a pioneer of railways, worked with English mining tramways that used various gauges. For his groundbreaking Stockton and Darlington Railway, he simply chose one that worked well: 4 feet, 8 inches.

This “Stephenson gauge” became the de facto standard due to network effects. By the time Great Britain considered a national standard, there were already 1,200 miles of his track in the ground, making it the logical choice.

The adoption in the United States was also not a simple inheritance.

While many early lines used the Stephenson gauge, others used different widths. The eventual standardization was largely a political and logistical outcome of the U.S. Civil War. The North, which predominantly used the 4 foot, 8.5 inch gauge, won the war and subsequently rebuilt much of the Southern railway system to match its own for strategic and economic reasons.

Finally, the dramatic conclusion about the Space Shuttle is a complete fabrication.

The story about the SRBs being constrained by a railway tunnel that is “slightly wider than the railroad track” is false.

Railway tunnels are built with significant clearance and this part of the tale was invented to give the legend a modern, awe-inspiring punchline.

The real danger isn’t the historical inaccuracy of the story, but why it’s so popular. The myth persists because it provides a simple, deterministic explanation for a complex system and it validates our natural aversion to what we perceive as arbitrary constraints.

It’s a story about path dependency, but a dangerously oversimplified one.

It encourages a simplistic “burn it all down” mindset, suggesting that all standards are arbitrary and stifling. It fails to distinguish between bad, outdated constraints and the good, enabling standards that are the true engines of progress.

Part 2: Standards as Innovation Engines

The “horses’ asses” story paints a picture of standards as a cage. The reality is that the right kind of standards are not a cage, but a scaffold - a structure that allows us to build higher, faster and more safely than we ever could in a state of chaos.

The key is to distinguish between two types of standards.

Prescriptive standards dictate a specific implementation and can stifle creativity. They tell you exactly what to do and how to do it. The myth frames the railroad gauge this way. But the great leaps in innovation have come from enabling standards.

These standards define a common interface, protocol or set of rules, creating a stable platform upon which creativity can flourish.

They don’t tell you what to build - they tell you how to connect to the system.

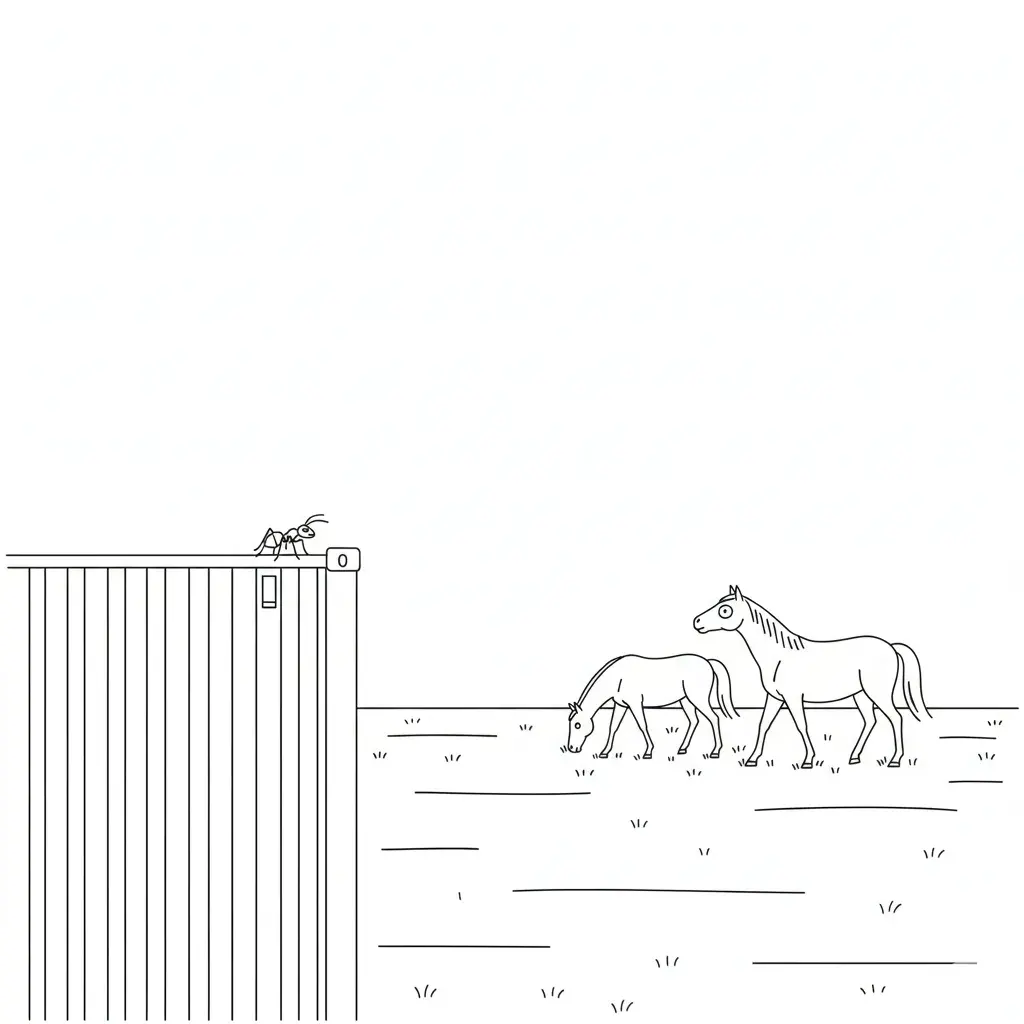

Before the 1950s, loading a ship was a chaotic, expensive and time-consuming process known as break-bulk shipping.

Goods were packed in sacks, barrels and crates of all sizes and manually loaded by teams of longshoremen. It could take weeks to load and unload a single vessel, with significant losses from damage and theft.

Then, a trucking entrepreneur named Malcom McLean had a simple but revolutionary idea: what if, instead of loading the cargo, you loaded the whole truck trailer onto the ship?

This evolved into the intermodal shipping container. The genius was not in the box itself, but in standardizing its dimensions. In 1968, the International Standards Organisation (ISO) set the familiar dimensions (initially 20 feet long, 8 feet high and 8 feet wide) and corner fittings.

This enabling standard created a seamless global logistics platform. The same box could be moved by truck, rail and ship without ever being unpacked.

It dramatically reduced port congestion, shipping time and costs. The impact was staggering. The shipping container “has been more of a driver of globalization than all trade agreements in the past 50 years together”.

The standard didn’t dictate what went inside the box - it created a reliable system that unleashed global manufacturing and trade.

In the digital world, the most important enabling standard is the Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol (TCP/IP).

Developed in the 1970s by Vint Cerf and Bob Kahn for a U.S. Department of Defense project, its goal was to create a way for different computer networks to communicate reliably.

The brilliance of TCP/IP lies in its layered simplicity. It provides a universal set of rules for how to do two things: TCP breaks data into small packets and ensures they are all reassembled correctly at the destination, while IP acts as the postal service, giving each packet an address and routing it through the network.

By providing this stable, universal “language”, TCP/IP created the platform upon which virtually all modern internet innovation was built.

Everything from email and the World Wide Web to cloud computing and video streaming relies on this foundational standard. It lowered the barrier to entry for innovators, who no longer had to worry about the underlying plumbing of the network.

They could just build.

This brings the argument directly into my world of software engineering.

Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) are the modern incarnation of enabling standards. An API is a contract that defines how different software components should interact, without either one needing to know the complex internal details of the other.

Well-defined API specifications, like OpenAPI, allow my teams to build complex systems faster and more reliably.

They let us avoid recreating the proverbial wheel by plugging into existing functionality.

We can use Stripe’s API for payments, Google’s API for maps or our own internal microservices APIs to build new features.

This enables parallel development, where teams can work independently on different components, confident that they will connect seamlessly as long as they adhere to the API “contract”.

Furthermore, these standards don’t just accelerate innovation - they create entirely new markets. Companies like AccuWeather and Stripe built massive businesses by monetizing access to their data and services through clean, well-documented APIs, giving rise to the “API economy”.

Here, the standard is not just an enabler of the product - the standard is the product.

Part 3: The High Care, High Performance - Choosing Your Poison

We’ve seen how enabling standards create the conditions for innovation. This brings me back to the retreat and its second, more insidious myth: the idea that a company can simultaneously achieve “High Care” and “High Performance”.

This is a comforting fiction that leaders tell themselves, but it ignores a fundamental law of systems and human nature: you cannot maximize two competing variables at once.

The tension between caring for people and holding them accountable to extreme performance standards is not something to be “balanced” - it is a direct trade-off.

To achieve one, you must be willing to sacrifice the other.

The corporate world loves to use the “elite athlete” as a model for performance, but they conveniently ignore what that model truly represents. An elite athlete is a case study in the complete and total sacrifice of “care” for the singular goal of “performance”.

Their lives are defined by what they give up. They sacrifice social lives, missing weddings, birthdays and holidays. They adhere to brutal training regimes and punishing diets, forfeiting simple pleasures. Their financial stability is often precarious and their personal relationships are strained by time and distance.

Australian field hockey player Matt Dawson amputated the tip of his finger to be able to compete in the 2024 Paris Olympics after a severe injury in a practice match. Surgery to repair the broken finger would have required months of recovery, so he chose amputation, which had a much shorter recovery time, to ensure he would be fit for his third Olympic Games.

This is the reality of peak performance. It is not a balanced life. It is a life where well-being, relationships and personal comfort are consciously and systematically sacrificed on the altar of results.

To pretend we can demand this level of performance from our employees without also demanding a similar sacrifice is naive at best and dishonest at worst.

In the business world, this trade-off manifests as burnout.

A culture that relentlessly prioritizes high performance inevitably creates an environment of high pressure, unrealistic expectations and a lack of psychological safety. The result is not a thriving, synergistic workforce, but a predictable cycle of exhaustion and turnover.

The most damning evidence is who gets hurt the most. It is consistently the high performers who are most vulnerable to burnout. The very traits that make them exceptional - their high standards, emotional investment and willingness to take on responsibility - are what drive them into exhaustion in a low-care system. This creates a performance-resilience gap, a dangerous state where your most productive employees have the lowest capacity to recover from stress, making them the highest risk for turnover.

The financial costs are staggering, with burnout costing businesses hundreds of billions annually in lost productivity and healthcare expenses.

This isn’t a system failure - it’s the system working as designed. A high-performance culture, by its very nature, treats human capital as a resource to be consumed in the pursuit of its goals.

The choice is not how to achieve both high care and high performance, but which to prioritize.

The evidence is clear that when the pressure is on, one will be sacrificed for the other.

This leaves leaders with a stark choice:

-

High Performance with Lower Care: This path pursues aggressive goals and accepts that burnout and turnover are costs of doing business. It optimizes for output, knowing that it will consume its most dedicated people in the process.

-

High Care with Lower Performance: This path prioritizes employee well-being, psychological safety and a sustainable pace. It fosters loyalty and stability but accepts that it may not achieve the same aggressive targets or market-beating results as its competitors. It avoids becoming an “all-care-no-responsibility” culture, but it consciously lowers the performance ceiling.

To pretend there is a magical third option where no sacrifice is needed is to set up your organization and your people for failure.

Conclusion: What Is Your Foundation?

The stories we tell ourselves matter. They shape our strategies, our architectures and our cultures.

We started with a folksy but false story - the “two horses’ asses” myth - that champions a chaotic, anti-standards view of innovation.

We dismantled it and saw that the real history of progress is one of pragmatic choices and enabling standards.

This leads to a final, more difficult truth.

The most popular story in corporate culture today is the myth that we can build an organization of “High Care and High Performance” without compromise. This is as dangerously misleading as the story about Roman chariots.

As leaders, we must choose our foundation with open eyes, acknowledging the inherent trade-offs.

-

We can build a foundation for High Performance. This means optimizing for results, speed and market dominance. It’s a culture that attracts and rewards elite performers but must accept the inevitable cost: a higher rate of burnout, employee turnover and the risk of a toxic environment where people are sacrificed for metrics.

-

We can build a foundation for High Care. This means optimizing for sustainability, psychological safety and employee well-being. It’s a culture that builds loyalty and retains talent but must accept that it may move slower and achieve less aggressive outcomes than its more ruthless competitors.

The greatest failure of leadership is not in choosing one path over the other, but in pretending you can have both.

Let’s discard the comforting myths. Let’s be honest about the sacrifices required for our ambitions.

Let’s build our foundations not on the asses of two long-dead horses or on feel-good corporate slogans, but on a clear-eyed understanding of the trade-offs we are willing to make for the results we want to achieve.