It’s Saturday afternoon. You’re armed with an Allen key, a set of instructions that might as well be written in ancient runes and a flat-pack bookshelf that looks nothing like the picture on the box.

Your kids, your “team”, are offering the kind of help that involves losing screws and drawing on the manual.

It’s a scene of controlled chaos, a project with shifting requirements and a highly unpredictable team.

If this feels strangely familiar to anyone who’s managed a high-pressure engineering sprint, you’re not alone.

That chaotic living room floor is a perfect microcosm of modern tech leadership. This realization is the heart of “Dad-Ops” - a leadership philosophy that argues the best way to manage the complex, data-driven world of engineering is by applying the simple, human-centric principles of being a good parent.

This isn’t about being paternalistic; it’s about recognizing that nurturing growth, resilience and autonomy is the most effective way to build teams that last

And let’s be honest, our industry needs yet another new playbook. The state of engineering in 2025 is shaky (when it wasn’t?). A staggering 68% of engineering managers felt burned out in the last year, thanks to a perfect storm of staff shortages, hybrid work adjustments and a shaky economy.

It’s even worse for developers. The latest Stack Overflow survey suggest that up to 90% of developers are unhappy, with one in three actively disliking their jobs. They’re drowning in technical debt, crushed by a relentless “hustle culture” and stuck in the mud of corporate bureaucracy.

The old way of managing for pure velocity is breaking people.

We need a more sustainable approach. In this playbook I will try to offer five principles, borrowed from fatherhood, that are more than just soft skills. Think of them as strategic, data-backed imperatives for building engineering teams that don’t just perform, but thrive.

Table of contents

Open Table of contents

Principle 1: Be the “Umbrella Parent”

Picture a father walking with his child in a sudden downpour. His first instinct is to hold the umbrella over his child, even if it means he gets soaked.

He doesn’t eliminate the storm, but he creates a protected space, shielding his child from its full force.

This is one of a leader’s most critical, yet overlooked, jobs.

Your role is to be the umbrella.

In the workplace, the “storm” is the constant barrage of organizational chaos:

- pressure from executives

- shifting stakeholder demands

- budget cuts

- endless corporate politics

A manager’s job is to absorb that storm and create an environment of psychological safety for their team. This isn’t about being “nice” or avoiding accountability. It’s about creating a culture of rewarded vulnerability - a space where an engineer feels safe enough to take a risk. A space where they can ask a “dumb” question, admit they broke the build or challenge a senior engineer’s design without fear of being humiliated or punished.

Teams that have this are not just happier; they are measurably better at innovating and solving problems

How to Be the Umbrella:

-

Pressure flows downhill. It starts in the boardroom and ends on your engineer’s laptop. Your job is to stand in the middle of that waterfall. Absorb the ambiguous requests, negotiate realistic deadlines and filter out the noise. Distill the chaos into a clear, manageable set of goals your team can actually achieve.

-

You can’t demand psychological safety - you have to model it. Be the first to admit you don’t know something. Be the first to own a mistake. When you, the leader, show that it’s okay to be imperfect, you give your team permission to do the same. Studies on leader humility show this is one of the fastest ways to build trust and creativity.

-

Things will break. Deployments will fail. The leader’s reaction to failure defines the culture. When something goes wrong, focus on the process, not the person. Run blameless post-mortem/learning that ask “what and how” and not “who”. This turns a moment of failure into a valuable lesson and prevents a culture of fear from taking root.

Without this protective umbrella, you create an invisible tax on every single interaction.

Good ideas go unspoken, bad ideas go unchallenged, and early warnings are ignored because everyone is too afraid to speak up.

A manager who fails to build this shield isn’t just being unsupportive - they are actively suppressing their team’s talent and paving the road to burnout!

Principle 2: The Art of Patient Observation

Ever watched a toddler get furious at a collapsing block tower? The impatient parent rushes in, grabs the blocks, and builds it “the right way”. The task gets done, but the child learns nothing except that they can’t do it themselves.

The “Dad-Ops” parent does something different. They sit with the child in their frustration. They watch. They ask questions. “What happens when you put that big block on top?” They let the child discover the solution on their own.

This is the difference between reactive direction and strategic diagnosis.

In management, this is the practice of Active Listening and Strategic Patience.

Active listening isn’t just waiting for your turn to talk - it’s a powerful diagnostic tool for understanding the real problem before you jump to a solution.

Patience isn’t just a virtue - it’s a performance multiplier.

Impatient leaders fracture relationships and make hasty decisions that almost always create technical debt.

How to Practice Patient Observation:

- Become a master listener - this is a skill you can learn.

-

Put your phone away. Close your laptop. Give the person your full focus

-

Your goal is to understand, not to critique/judge

-

Say things like: “So, what I’m hearing is…” to confirm you’ve understood

-

Ask open-ended questions: “Can you tell me more about that?”

-

Briefly restate the key points

-

Only after you’ve done all of the above should you offer your own perspective

-

In your next one-on-one, try waiting a full three seconds before you respond. This simple trick stops you from interrupting and gives the other person space to finish their thought. It feels weird at first, but it’s incredibly powerful.

-

”Why is this late?” puts people on the defensive. “What obstacles are getting in our way?” invites collaboration. This small change in language can transform a conversation from blame to problem-solving.

A leader’s impatience creates a vicious cycle. It leads to rushed decisions, which creates technical debt.

Working in a codebase full of tech debt is a top driver of developer burnout.

Burnout leads to missed deadlines, which only fuels the leader’s impatience, and the cycle continues. Patience isn’t about moving slowly - it’s about making sure you’re moving forward sustainably

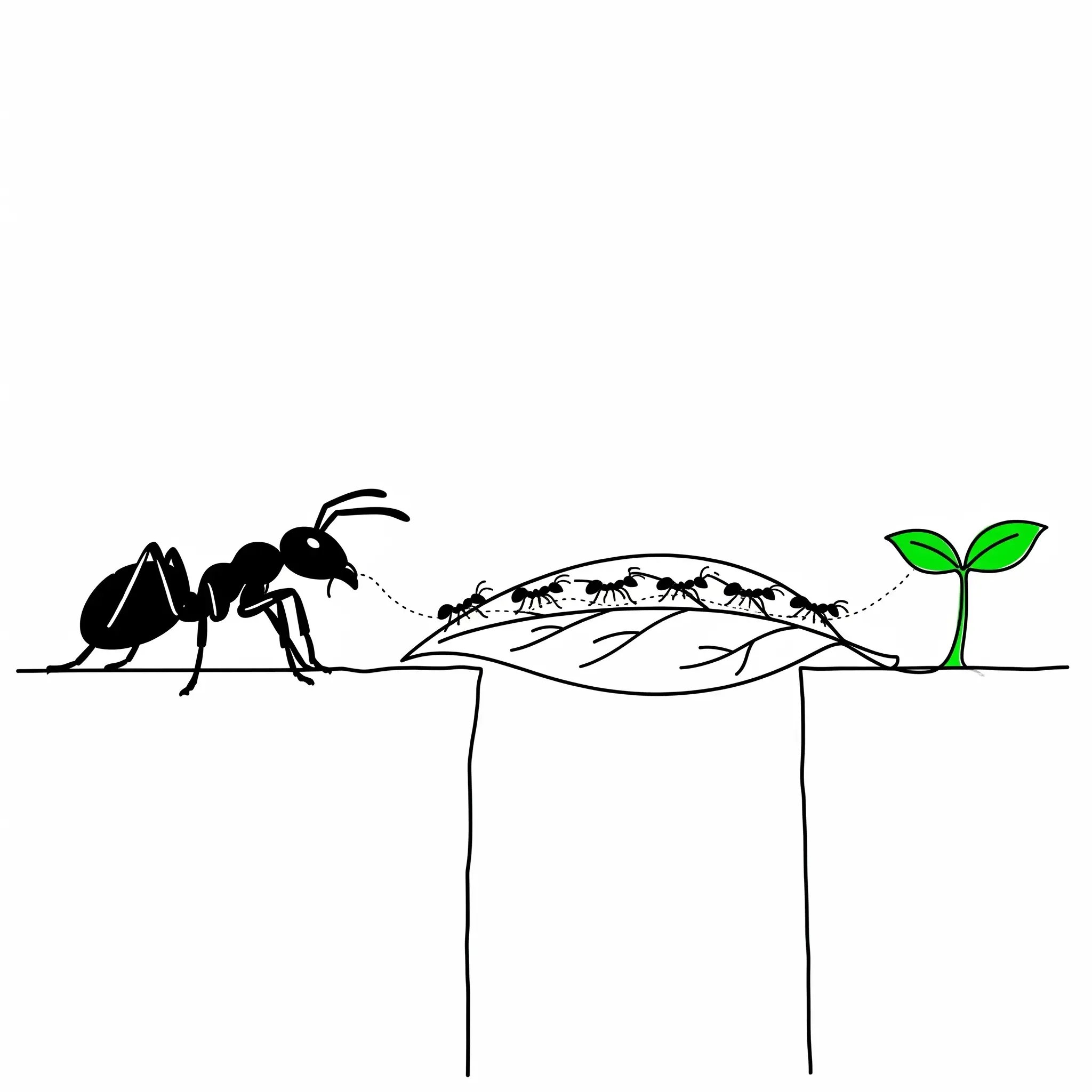

Principle 3: Let Them Scrape Their Knees

Remember learning to ride a bike? There’s a terrifying, exhilarating moment when the parent has to let go of the seat. The child will wobble. They will probably fall. They might scrape a knee. But that moment of letting go is where the real learning happens.

It’s through that cycle of trial, failure, and getting back up that a child builds the skill and confidence to ride on their own.

The opposite of this is micromanagement, and it is poison to an engineering team.

60% of employees say they’ve been micromanaged. Of those, 55% said it hurt their productivity and a whopping 70% said it crushed their morale.

For an industry with a talent shortage, this next stat is a killer:

40% of people have changed jobs just to escape a micromanager.

The antidote is empowered autonomy. You should not abandon your team - no, but instead you should shift from delegating tasks to delegating outcomes.

Give them the destination and trust them to draw the map.

This is especially critical for retaining senior engineers, who are driven by the freedom to solve complex problems their own way.

How to Let Go of the Bike Seat:

-

Your job is to provide crystal-clear context. What is the goal? Why does it matter to the business? Once that’s clear, step back. Let the experts - your engineers - figure out the best way to build it. They’ll come up with better solutions and feel a powerful sense of ownership over the result.

-

Frame your guidance as an apprenticeship, especially with junior engineers. Clearly define the areas where they have the authority to make decisions. When they make a mistake, treat it as a coaching moment, not a failure. As they grow, intentionally expand their scope of autonomy.

-

The urge to jump in and solve a problem for your team is strong. Resist it. The most helpful managers watch, listen and let their people struggle a bit first. Help is most appreciated when someone has already wrestled with a problem and truly needs a hand. Intervening too early just feels like a lack of trust.

Micromanaging senior engineers is one of the fastest ways to destroy a high-performing team. It leads to something called the “Dead Sea Effect” - where the most talented people evaporate, leaving behind a more concentrated pool of mediocrity.

The best engineers have the most options - they will not tolerate being treated like a junior coder. They will leave.

The engineers who are less confident or have fewer options will stay. Over time, your team’s average talent level will drop, all because you couldn’t let go of the bike seat.

Principle 4: The Chore Chart Principle

There’s a strange magic to a simple chore chart on a refrigerator. A kid who complains about cleaning their room will suddenly do it with enthusiasm for a single gold star. The star has no cash value, but its power is immense. It makes progress visible. It makes effort feel acknowledged. It builds momentum.

This household tool perfectly illustrates one of the most powerful discoveries in workplace psychology: the single most powerful motivator at work is making consistent, meaningful progress-even small wins.

These small wins fuel our “inner work life” - the daily mix of emotions and motivations that drives performance.

When we feel like we’re moving forward, we’re more creative, productive, and engaged.

It even triggers a dopamine hit in our brains, making us want to achieve the next win.

A manager’s job is to be a “catalyst” for that progress by removing obstacles and a “nourisher” of the people doing the work by offering encouragement and support.

How to Build the Chore Chart:

-

A six-month project with no visible milestones is a recipe for demoralization. Work with your product manager and senior engineer to break down huge projects into small, achievable tasks that can be completed every few days. Each closed ticket is a gold star that refuels the team’s motivation.

-

Start your day by asking two questions: (1) “What one thing can I do today to catalyze progress for my team?” (e.g. unblock a PR, get an answer from another team). (2) “What one thing can I do to nourish them?” (e.g. give a specific piece of praise in Slack, check in on someone who seems stressed).

-

Don’t wait for the big release party to celebrate. Acknowledge the small victories along the way. A shout-out for a clever refactor, a nasty bug fixed, or a well-written piece of documentation shows that you value the hard work that happens every day.

Setbacks are more powerful than wins. A single frustrating blocker can wipe out the positive feelings from a week of small victories.

This means a manager’s most important job is to be an inhibitor remover. Your primary function is to aggressively clear the path for your team.

The inhibitors are everywhere:

- ambiguous requirements

- a flaky CI/CD pipeline

- merge conflicts

- the soul-crushing friction of technical debt

The most effective managers aren’t the ones in endless strategy meetings - they’re the ones in the trenches, making sure the path to the next gold star is as smooth as possible.

Principle 5: Building the Treehouse

You don’t hand a child a detailed architectural blueprint to build a treehouse. You give them a pile of wood, a hammer, some nails and a safe space in the backyard to figure it out. The result might be a little crooked, but the value isn’t in the finished product. It’s in the process - the creativity, the problem-solving and the learning that happens along the way.

This is how you should think about innovation on your team. If your team is running at 100% capacity just to keep up with the roadmap, you have zero capacity for innovation. Their skills will stagnate, and your product will fall behind. This is more critical than ever in the age of AI. As AI tools get better at writing routine code, the most valuable human skills will be creative problem-solving and high-level architectural thinking.

A team that isn’t given the space to develop these skills is being managed for obsolescence.

Do you remember Google implemented “20% of time”? It’s not a perk - it’s a survival strategy.

How to Supply the Wood and Nails:

-

Formally block out time on the calendar for non-roadmap work. It could be “Fix-it Fridays” - a dedicated hack day each sprint or an innovation week each quarter or hackathon end of quarter. This time is sacred. Defend it from encroachment as fiercely as you would your most critical production deadline.

-

Create a culture where experiments are encouraged, even if they fail. Frame these projects as data-gathering exercises, not pass/fail tests. The goal is to learn something new. This lowers the fear of failure, which is the biggest killer of innovation.

-

A tangible budget for books, online courses or conference tickets sends a powerful message: learning is part of the job, not something you have to do on your own time. This investment pays for itself by bringing new ideas and skills back to the team.

In the age of AI, giving your team this “treehouse time” is the single best way to future-proof their careers and your business.

AI is going to automate much of the routine coding that junior engineers have traditionally used to build their skills.

If you don’t create a space for them to learn in other ways, you are actively creating a skills gap on your own team.

A team that is 100% focused on this quarter’s features is becoming less valuable with every sprint that passes.

This strategy transforms your team from a short-term feature factory into a resilient, adaptive system built for the long haul.

Conclusion

The five principles of the Dad-Ops Playbook(the “Umbrella Parent”, practicing “Patient Observation”, letting them “Scrape Their Knees”, using a “Chore Chart” and “Building the Treehouse”) - are more than just parenting analogies.

They are a practical framework for solving the deepest challenges in engineering leadership. They work together to create an environment where talented people can do their best work.

You can’t have autonomy without psychological safety. You can’t remove blockers if you haven’t patiently diagnosed the real problems.

Ultimately, the fatherhood metaphor clarifies the true purpose of leadership. Good parenting is not about optimizing for a perfect report card this semester - it’s about raising a capable, resilient and independent human who will thrive long after you’re gone.

Likewise, great engineering leadership isn’t about hitting this sprint’s velocity target at all costs. It’s about building a capable, resilient and autonomous team that can solve tomorrow’s problems, long after you’ve moved on to your next role.

It’s about building a legacy.

So, the final question for every leader is a simple one: Are you managing for the next deadline or are you leading for the next decade?

Appendix 1

The Dad-Ops Playbook: At a Glance

| Fatherhood Principle | Core Management Concept | Key Leadership Action |

|---|---|---|

| Be the “Umbrella Parent” | Psychological Safety | Shield the team from organizational chaos and model rewarded vulnerability |

| The Art of Patient Observation | Active Listening & Patience | Use deep listening as a diagnostic tool before acting - cultivate patience to improve team outcomes |

| Let Them Scrape Their Knees | Empowered Autonomy | Delegate outcomes, not tasks - trust your team and treat failures as learning opportunities |

| The Chore Chart Principle | The Progress Principle | Structure work for small wins, remove blockers and consistently recognize progress |

| Building the Treehouse | Space for Innovation | Deliberately allocate time and resources for experimentation, learning and creative problem-solving |